On March 19, various media outlets began reporting that Taiwanese computer giant Acer had been hit by a REvil ransomware attack. While ransomware is nothing new, this attack is notable in two key respects. First, the size of the ransom demand: $50 million, the largest known cyber ransom demand in history. Second, the fact that this attack went beyond the standard file encryption.

The REvil attackers did encrypt large swaths of Acer files. But before they encrypted files, they exfiltrated them. That gives these attackers the standard leverage commonly used in ransomware attacks: Acer may need a decryption key to access the data and systems they need to run their business. It also adds a second challenge for Acer: How to stop proprietary and customer data—now in the hands of attackers—from being leaked.

Ransomware: Explanation and prevention.

Ransomware Trend: Exfiltration and Encryption

Exfiltration before encryption is becoming increasingly popular because it gives victims two reasons to pony up the ransom: They need to both regain access to their files and attempt to prevent leaks of their data. While Acer may be the first major ransomware attack victim to make headlines in this type of attack, they're not the only ones to be hit with this kind of two-pronged attack.

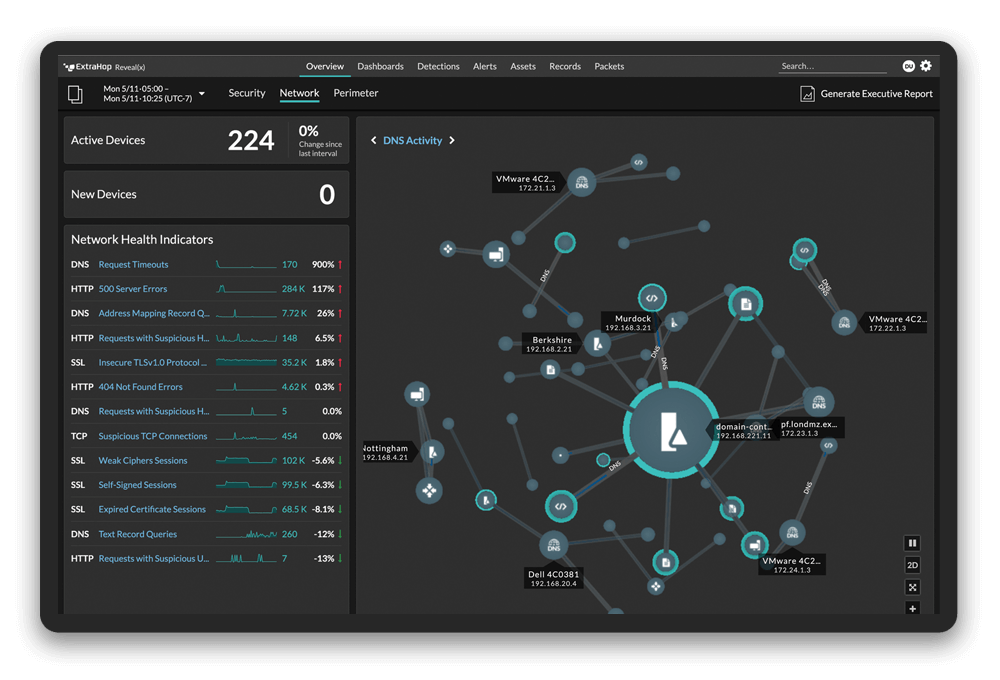

In late 2020, a large ExtraHop customer based in North America was alerted to a Ransomware Activity detection in Reveal(x) 360. The same devices were also seeing alerts for detections on SMB data staging and suspicious file reads—both telltale signs of a ransomware attack. The team was able to quickly identify and quarantine affected assets and accounts, and as a result, the attackers were only able to encrypt a small percentage of targeted files.

When looking into the ransomware activity, the customer's security team also uncovered another type of malicious activity: exfiltration. In this case, attackers were using a reverse shell with the same external IP where data was being exfiltrated, triggering both unusual interactive traffic and external data exfiltration detections in Reveal(x) 360. The team was able to use the Related Detections capability within ExtraHop Reveal(x), which clearly linked the encryption and exfiltration together as one concerted attack.

Learn more about detections, including the Related Detections feature.

As in the case of the Acer, the ransomware attackers were attempting to give themselves two potential avenues by which to force a ransom payment. If the company had backups and didn't need the encryption keys, the attackers could fall back on demanding payment in exchange for deleting the exfiltrated files.

Unlike Acer, however, the customer was able to quickly identify the ransomware attack in progress, determine what assets were affected, and identify related activity before millions of files could be stolen and then locked.

Our customer's internal and external IR teams also relied on ExtraHop during the post-incident investigation, using network metrics provided by ExtraHop to gain a comprehensive understanding of what data was exfiltrated before the attack was shut down, and make informed decisions about how to proceed.

As for Acer, so far, the company has kept fairly mum on the specifics of the attack, but reporting from Bleeping Computer and other sources has strong evidence in support of the exfil/encrypt two-pronged attack pattern.

However, there's still a lot of uncertainty surrounding other details. Bleeping Computer and other sources are also reporting that REvil attackers targeted an Exchange Server in Acer domain space. If true, this would be the first concrete example of the Exchange Server vulnerability CVE-2021-26855 being weaponized in a ransomware attack.

Read: Monitoring encrypted traffic matters for zero days like the Exchange Server exploit.

Another possible element to this attack involves supply chain exploitation. According to communications between Acer representatives and the REvil operators, the attackers warned that Acer could be the next SolarWinds. The good news is that this is not likely.

Just encrypting files and exfiltrating data, even Acer's source code, wouldn't allow them to perpetrate a SolarWinds-style supply chain attack. For that, they would need to have compromised Acer's build or update systems. At this point, odds are that is just a scare tactic intended to increase the odds of getting the ransom paid.

Still, the prospect of a multi-vector attack that involves encryption, exfiltration, and supply chain exploitation is an alarming one. It's a cyber attack hat trick, and a worst-case scenario for any organization.