The SolarWinds Orion SUNBURST supply chain attack has rocked the confidence of many security teams across industries. This two-part blog series is an examination of the attack by Todd Kemmerling, Director of Data Science at ExtraHop, to reconstruct the timeline of the attack over the past 9+ months and provide insights about how to improve threat detection in the future.

Part 1: A forensic examination of SUNBURST before detection

Over the last week I have been working on analyzing the depth and breadth of the SUNBURST trojan. I decided it was important to devote some time to understanding how this threat made it past so many, and was able to linger for so long, in the hopes of improving how we approach threat detection in the future.

In addition, I noticed that some of the forensic data is disappearing from public archives and databases and I wanted to preserve what I could. For example, the WHOIS record no longer lists the registrar of the last changes to avsvmcloud[.]com domain prior to Microsoft capturing the domain in a sinkhole.

Threat Level 0.25 (Unlikely)

On July 25, 2018 the domain name avsvmcloud[.]com was registered by a domain name squatter or typo squatter.

![Domain information for avsvmcloud[.]com](https://assets.extrahop.com/images/blogart/sunburst-origin/domain-info.png)

We can make this conclusion because there was nearly zero activity or social networking (such as a website or mentions on LinkedIn) on this domain until the recent past and the domain reseller activity is detectable back to early 2019.

A simple search (done on December 15, 2020) of the Wayback Machine showed only a single entry from 2019 where it appeared that robots.txt prevented the site from being indexed:

![Domain for avsvmcloud[.]com not indexed](https://assets.extrahop.com/images/blogart/sunburst-origin/domain-not-indexed.png)

It is not unusual for a new website to hold off indexing during development. Shortly after this entry was logged, the domain went up for sale. Here are some examples of the ads that listed avsvmcloud[.]com for sale:

![Ad listing avsvmcloud[.]com for sale](https://assets.extrahop.com/images/blogart/sunburst-origin/domain-for-sale.png)

Ad listing avsvmcloud[.]com for sale.

At this point the domain doesn't show anything to be concerned about:

- It looks like it could have been purchased as an investment (buy for low cost, sell for a profit)

- It has a near-zero footprint (only a couple of IP addresses and no links in or out)

- The observed IP addresses associated with the domain are from domain resellers and their hosting services

- The social graph (employee names, email address, phone numbers, web pages, IP addresses, web site) of the domain is small

On a scale of 0.0 (0% probability of threat) to 1.0 (100% probability of threat), I would score this risk level at 0.25 (or, most likely not a threat). It is not unusual for domains to be purchased and held—I do this on occasion myself for research purposes and for possible future projects.

Threat Level 0.375 (Inconclusive)

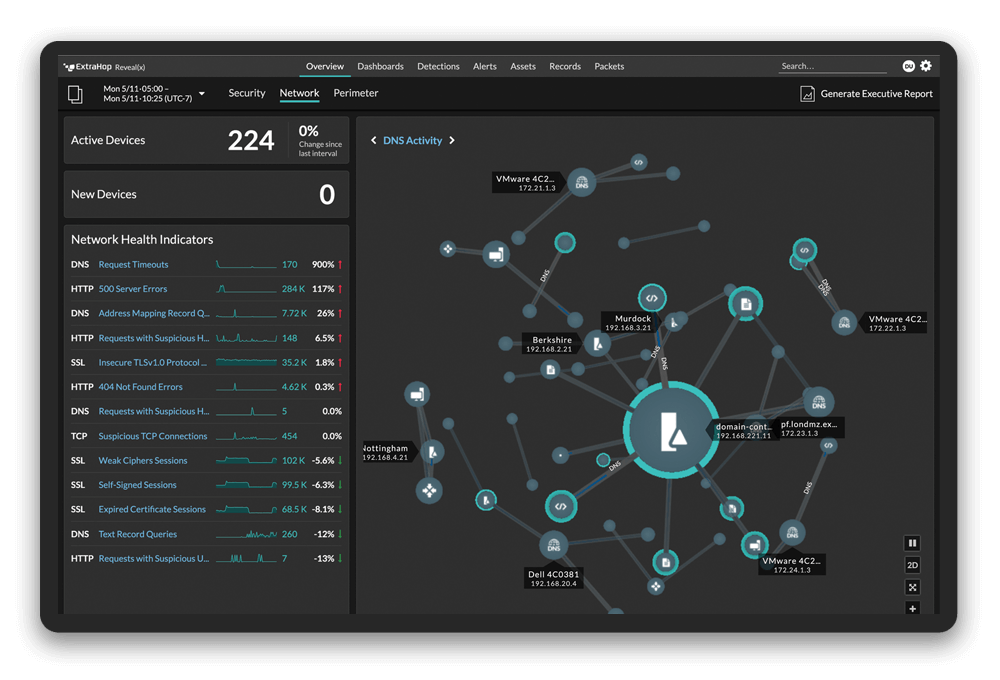

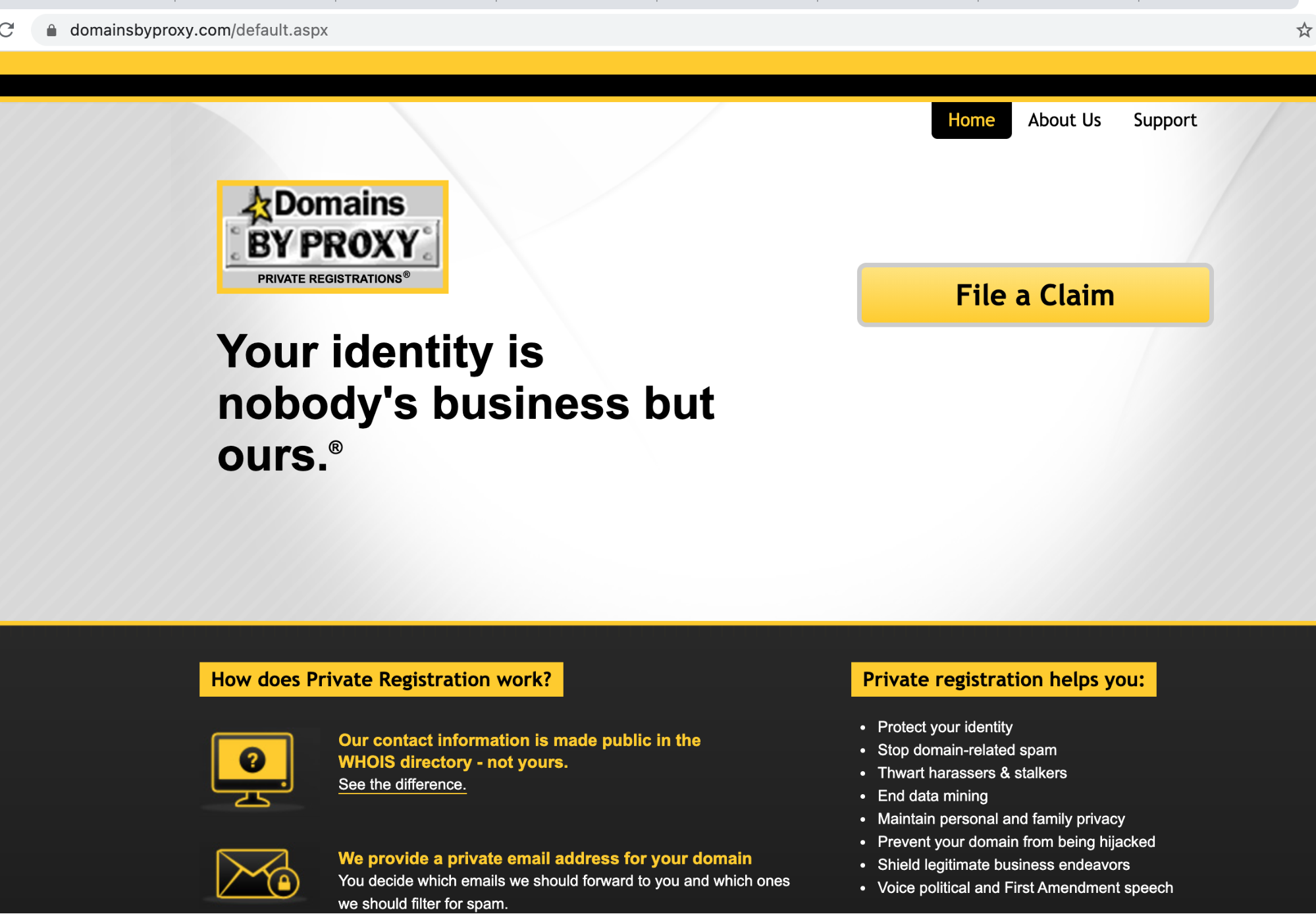

On February 25, 2020, the avsvmcloud[.]com domain was transferred and registered by www.domainsbyproxy.com, as confirmed by a WHOIS query on December 13, 2020 and by a number of other OSINT sources such as Domain Status.

It is not uncommon for a domain to transfer ownership, but it is a little unusual for a domain to sit dormant for two years, abruptly change ownership without any related relevant activity, and then immediately become active.

As avsvmcloud[.]com becomes more active, it can be considered a new domain because it has been parked for the bulk of its existence. Newly active domains are considered more risky than older established domains. The threat potential is still low, but moving from "not a threat" to "unknown threat." I would score the risk level at 0.375.

In retrospect, it becomes clear that lying dormant was a strategic effort by the SUNBURST trojan to avoid detection. In other words: go active, establish history, but take no note-worthy action.

Threat Level 0.50 (Growing)

On February 26, 2020, the SUNBURST trojan came to life. In a matter of minutes, the avsvmcloud[.]com domain grew from a single IP address to seven IP addresses. These IP addresses are from multiple cloud vendors located in Europe and the United States. In the next few days, the associated IP addresses grew to at least 15 locations on servers from at least three cloud service providers.

From a predictive modeling perspective, this is the worst position to be in. We know a threat is out there, we know it is active, we know it is growing, but we don't know enough to know what else might be coming. Based on the increased activity, I would score the risk level at 0.50.

Threat Level 0.90 (Imminent)

On April 15 a domain-generation algorithm (DGA) was observed with a fully-qualified domain name (FQDN) of f526qtbk9bbb9chpf1vt24i.appsync-api.eu-west-1.avsvmcloud[.]com. Based on the increased activity, I would score the risk level at 0.90.

Active Undetected Threat

When indicators of compromise began to appear in December, the security community was alerted and threat hunters began to see the scope and depth of the attack.

Why Is This Type of Detection Challenging?

While the December 13, 2020 FireEye Blog Post describes a DGA as a "domain name generated by algorithm," I prefer to characterize this FQDN as a "hostname generated by algorithm."

The "avsvmcloud" part of the FQDN determines whether the domain is a DGA. The hostname "f526qtbk9bbb9chpf1vt24i" part of the FQDN is not typically evaluated because it is not uncommon for large enterprises to assign hostnames by algorithm. The variables in this domain name are the algorithm-based hostname and region-based subdomains. Strictly speaking, the domain name is not changing and therefore there is nothing to detect.

The variables in the region-based subdomains appear to be a mechanism to minimize the chance of detection by "impossible distance" detections. These detections examine the locations where a user is logging in from and considers whether it is possible for that user to have traveled between those locations. For example if user "Todd" logs into the system from Paris and then logs in from San Francisco two hours later, an impossible distance detection occurs. These variable subdomains likely routed victims to more local attacker nodes.

If the variable subdomain successfully avoids the impossible distance detection, and there are no strong indicators that this FQDN is a threat, what are some other signals? We must look at unusual behavior signals.

What Should Security Analysts Do?

The first time this FQDN connects to a network, the incident should be detected as an unusual behavior. Unusual doesn't necessarily mean bad, but should be investigated. New FQDNs are frequent, researching them takes time, specialized tools, and access to the proper data.

When an investigation about a FQDN returns virtually no results (no web site, no business address, no CEO, no phone numbers except the domain registrar), you should consider this to be a strong signal that something is awry.

An ambiguous domain isn't a threat until an unknown actor on the internet is connecting to your network. While it is possible that this situation is benign, it is suspicious enough to be considered a legitimate potential threat.

References

The dataset in this analysis has at least two sources for each referenced data point, but should still be considered incomplete because we have ~1700 data points for an attack believed to have a footprint of nearly 18,000 systems.

Read the SUNBURST Origin Story Part 2: A Forensic Examination of SUNBURST After Detection